‘Atom and the Nuclear Hoax – FLAT FACT’ is a riveting video that challenges our preconceived notions about scientific concepts that we often take for granted, like the existence and observable nature of atoms. The video begins with a powerful statement – ‘No human has ever seen a real atom’. A fact that rings true even though it might be uncomfortable for many to acknowledge.

The video uses a clever blend of historical and current references, sprinkling just the right amount of humor, to provoke thought about the widely accepted narrative of atomic theory. Starting from the history of atomic theory with Democritus in 340 BC, the video traces the evolution of our understanding of the atom and the scientific breakthroughs that led to nuclear energy and weaponry. It puts into perspective how our faith in science and the scientific community can sometimes make us overlook the complexities and uncertainties inherent in scientific theories.

The video then delves into the ‘atomic’ vs ‘nuclear’ terminology debate, questioning whether this change was based on new scientific evidence or rather an attempt to reinvent the narrative. It leaves us to ponder why the term “atomic weight” has now been replaced with “atomic mass”, and the periodic table now looks considerably different. This shift in scientific understanding is worth considering, especially in light of the broader context of the video.

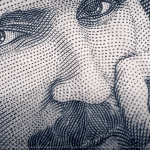

The comparison between the 1940s comic book character “The Atom” and the atom as we understand it today is a smart illustrative tool. It points out that every image we see of the atom is merely an artistic representation – a ‘cartoon’ in the truest sense. This creative analogy provides a tangible image to ground the abstract ideas the video is addressing.

The video then presents a hard truth: we have never, and probably will never, actually see an atom. It explains how the atomic force microscope is not an optical tool instead, it converts wave data into an image. The fact that no human has ever physically seen an atom makes you question the basis of our atomic knowledge.

In its conclusion, the video segues into the realm of quantum theory and quantum computing, suggesting that these might not be as firmly grounded in the solid reality of atomic particles as we believe, but rather in the intangible world of light. This is an interesting point to end on and leaves the viewer intrigued about the implications of this idea on our understanding of quantum phenomena.

‘Atom and the Nuclear Hoax – FLAT FACT’ does not claim to have all the answers, but it urges viewers to approach the established scientific consensus with a critical and questioning mindset. It prompts you to think about the information you have been presented with and consider whether it is a ‘flat fact’, an unassailable truth, or a concept open to interpretation and discussion. As such, it is a valuable resource for anyone interested in the history and philosophy of science, critical thinking, and the pursuit of knowledge.